My junior year of college, I finally took a film production class. Before that, I was pre-med and miserable in it. Biochemistry 330 was the final nail in the coffin and I jumped ship second semester. Although I didn’t or couldn’t put words to it, that winter of ’97-98 was an incredible turning point for me, leading me down the path to… well, not exactly glory. But not yet ruins, either.

No longer saddled with extra science courses, I stocked up on film theory and production as much as I could in my final three semesters of college. One theory course I took was taught by Professor [first name redacted… I mean, forgotten…] Cohen, who conducted, still to this day, the most interesting Film Theory course I’ve ever taken. It was a lecture course and simply called “Introduction to Film.”

At the beginning of the first class, Professor Cohen said something to the effect of: “If you like going to movies and might be concerned that knowing how movies are made will negatively affect your enjoyment or viewing of them – drop the course.” I love this advice. It’s like knowing how a magic trick works, I guess. Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain… er, camera.

The films we watched in that class were incredible. They ranged from the elegant Chinese film Raise the Red Lantern to the elegant American film Terminator 2: Judgment Day. (There are painfully few Austrian body-builders in Raise the Red Lantern, I must say.)

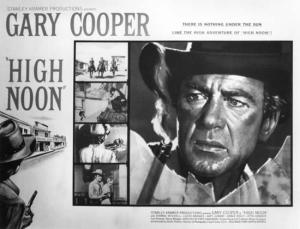

Several of the films I watched in that class fit into my requirements for re-visiting. But one stands out in my mind as a personally transformative piece of cinema – High Noon. Directed by Frank Zinnemann and written by Carl Foreman (who was booted from the production and fled to London after being blacklisted by cowardly jackasses).

Several of the films I watched in that class fit into my requirements for re-visiting. But one stands out in my mind as a personally transformative piece of cinema – High Noon. Directed by Frank Zinnemann and written by Carl Foreman (who was booted from the production and fled to London after being blacklisted by cowardly jackasses).

The title of this weblog entry (seen above) is taken from the Oscar-winning original song that plays in the opening credits – “Do Not Forsake Me, Oh My Darlin'” the refrain goes. And I can’t even think about High Noon without hearing that song in my head. It’s old-timey and sounds like it would be from the era in which the film takes place. And the musical score, a variation of the theme, is used to incredible effect in the film – more so than almost any film I can think of. (I don’t really know how to describe music in word form but I’ll do my best.)

The score (also Oscar-winning) is very methodical, a precise beat that prods and moves along, unyielding. It’s used throughout, but as the film progresses, the beat increases tempo (look there – a musical word!) as the tension increases.

This is probably true in other films but the reason why it works in High Noon is because of something the title itself implies: Time.

The film takes 85 minutes to tell. The events of the film are in real time and take the exact amount of time to unfold on the screen. It is incredible.

This is before computer editing (obviously) that allowed for trial and error. So aside from the extremely tight storytelling, this is an amazing feat of technical filmmaking, especially for 1952.

Time. Time is everything in the film. (Even the judge’s last name, as seen on a sign, is “Mettrick.” This must be deliberate, a subtle reminder of a steady and measured pace.) In 85 minutes, Frank Miller (Ian MacDonald) is coming off the noon train and he’s pissed. And Marshal Will Kane (Gary Cooper), the man who sent Miller to prison, has to gather forces to make sure the outlaw doesn’t return and destroy the peace Kane created.

Time. Time is everything in the film. (Even the judge’s last name, as seen on a sign, is “Mettrick.” This must be deliberate, a subtle reminder of a steady and measured pace.) In 85 minutes, Frank Miller (Ian MacDonald) is coming off the noon train and he’s pissed. And Marshal Will Kane (Gary Cooper), the man who sent Miller to prison, has to gather forces to make sure the outlaw doesn’t return and destroy the peace Kane created.

Which would be easier in normal circumstances, but it’s Kane’s wedding day to Amy Fowler (pre-Princess Grace Kelly) and he’s about to leave town. After the ceremony and right before he and Amy get ready to leave, Kane expresses concern that the new marshal* hasn’t yet arrived. Moments later, the telegram arrives warning that Frank Miller’s a-comin’. Everyone knows it’s to kill Kane – the man who cleaned up the town, a hero to the citizens there.

Which would be easier in normal circumstances, but it’s Kane’s wedding day to Amy Fowler (pre-Princess Grace Kelly) and he’s about to leave town. After the ceremony and right before he and Amy get ready to leave, Kane expresses concern that the new marshal* hasn’t yet arrived. Moments later, the telegram arrives warning that Frank Miller’s a-comin’. Everyone knows it’s to kill Kane – the man who cleaned up the town, a hero to the citizens there.

Kane and Amy are quickly scuttled away, put on their packed-up wagon, and in a flash they’ve left town. But Kane stops before he gets too far and realizes that this is his fight. He cleaned up this town, he’ll be damned if the man he kicked out comes back and everything us undone. So he assumes, in the 80 or so minutes before the train arrives, he can gather up a posse of citizens to join him and fight. But as he goes around Hadleyville trying to amass a force, he’s met with scorn, incompetence, and worst of all – indifference. After all, Kane is technically no longer marshal as of that day and Miller’s beef might be just with Kane. If Kane goes, then perhaps Miller won’t do anything at all. So the church goers, the saloon patrons who miss Miller’s lawless reign, and even his deputy who said he would help – all of them turn out to be unwilling or unable.

The only one who wants to fight is a young boy, and there’s no way Kane will let a boy risk his young life. So the clock ticks, and it’s just Kane.

(*Did you realize “marshal” is spelled with one L? Doesn’t that look weird to you?)

“I’VE GOT TO, THAT’S THE WHOLE THING”

Kane is one of my favorite film heroes in any film ever. His main character trait is commitment to duty. He has a job and an obligation and is bound by it – to the point of his own destruction. This reminds me of how I was raised to understand Lord Rama, hero of the South Asian epic “The Ramayana.” Having grown up in the Hindu tradition, I studied and was really drawn to Rama – a celestial incarnation who has superhuman powers but is mortal and bound to a deep sense of duty.

Kane is one of my favorite film heroes in any film ever. His main character trait is commitment to duty. He has a job and an obligation and is bound by it – to the point of his own destruction. This reminds me of how I was raised to understand Lord Rama, hero of the South Asian epic “The Ramayana.” Having grown up in the Hindu tradition, I studied and was really drawn to Rama – a celestial incarnation who has superhuman powers but is mortal and bound to a deep sense of duty.

In “The Ramayana,” Rama is frequently described as dharma personified. “Dharma” is “duty” (“Dharma” is also the name of a bad ’90s sitcom character and probably countless children of hippies). Rama’s dharma is as a prince, a son, and as a warrior. But this frequently puts him in a sticky situation, this deep commitment to duty. Rama’s father, King Dasharatha, (against his own wishes but for reasons that are too complex to get into here) asks Rama to go into exile to the forest and renounce the throne and riches and everything. Because he’s bound to follow his father’s wishes, he goes without hesitation. But Rama’s father soon dies from heartache and an old forgotten curse.

In “The Ramayana,” Rama is frequently described as dharma personified. “Dharma” is “duty” (“Dharma” is also the name of a bad ’90s sitcom character and probably countless children of hippies). Rama’s dharma is as a prince, a son, and as a warrior. But this frequently puts him in a sticky situation, this deep commitment to duty. Rama’s father, King Dasharatha, (against his own wishes but for reasons that are too complex to get into here) asks Rama to go into exile to the forest and renounce the throne and riches and everything. Because he’s bound to follow his father’s wishes, he goes without hesitation. But Rama’s father soon dies from heartache and an old forgotten curse.

Kane, in High Noon, is bound to protect the town. But he’s also bound to his new wife. What about her? If he protects the town, if he chooses to abandon her on their wedding day and risk his life, his wife won’t fight with him. She’s a Quaker, sworn to nonviolence (hey there – another connection to Hinduism!) and potentially will be widowed. He chooses an earlier, “greater-good” obligation and duty. But that doesn’t make it easier to swallow for Amy.

This question of duty is fascinating in High Noon and doesn’t only apply to Kane. What’s Amy’s responsibility? Should she stand by her man? What about her own faith and moral compass?

This question of duty is fascinating in High Noon and doesn’t only apply to Kane. What’s Amy’s responsibility? Should she stand by her man? What about her own faith and moral compass?

A great character in this town is the Mexican businesswoman/former Kane lover, Helen Ramirez (Katy Jurado). She scolds Amy thusly (again – WordPress’s best effort in script format):

HELEN What kind of woman are you? How can you leave him like this? Does the sound of guns frighten you that much?AMY I've heard guns. My father and my brother were killed by guns. They were on the right side but that didn't help them any when the shooting started. My brother was nineteen. I watched him die. That's when I became a Quaker. I don't care who's right or who's wrong. There's got to be some better way for people to live. Will knows how I feel about it.

So now – we have Kane in town and no one is going to help him. His wife is going to leave on the same train Miller’s coming in on. Kane goes to the church and it looks like people are going to rally behind him, reminded of his work cleaning up Hadleyville. Then, steadily, people say – hey, it’s not our job to fight. The minister throws in his $0.02 and it comes up as so:

DR. MAHIN, MINISTER The commandments say 'Thou shalt not kill,' but we hire men to go out and do it for us. The right and the wrong seem pretty clear here. But if you're asking me to tell my people to go out and kill and maybe get themselves killed, I'm sorry. I don't know what to say. I'm sorry.

Even his former Deputy Sheriff (Lloyd Bridges), mad at Kane for not giving him the promotion to marshal, tries to convince his old mentor Kane to leave town – to the point of drunken fighting him to get his point across (it doesn’t work).

So Kane is alone. Amy is at the train station – she sees Miller’s gang waiting for that same train to arrive with Frank Miller. Kane thinks he’s going to die. He even sits down and writes his final will. And then, this incredible montage sequence happens. It’s triggered by Kane’s initial scratching on the paper. THEN, holy cow, it’s really intense. A driving, pushing crescendo of a montage – the music rising more and more as the cuts (still shots almost) get tighter and tighter, giving us an overview of everyone we’ve met in town – the folks at the bar, the church (some with expressions of regret or fear), the people betting against him, Miller’s criminal cronies, the inn keeper, the judge who sent Frank Miller away, Helen, Amy, different intense angles of clocks and pendulums, all building up to the dolly in we saw earlier of the chair Miller was sentenced in. And then the train whistle!

So Kane is alone. Amy is at the train station – she sees Miller’s gang waiting for that same train to arrive with Frank Miller. Kane thinks he’s going to die. He even sits down and writes his final will. And then, this incredible montage sequence happens. It’s triggered by Kane’s initial scratching on the paper. THEN, holy cow, it’s really intense. A driving, pushing crescendo of a montage – the music rising more and more as the cuts (still shots almost) get tighter and tighter, giving us an overview of everyone we’ve met in town – the folks at the bar, the church (some with expressions of regret or fear), the people betting against him, Miller’s criminal cronies, the inn keeper, the judge who sent Frank Miller away, Helen, Amy, different intense angles of clocks and pendulums, all building up to the dolly in we saw earlier of the chair Miller was sentenced in. And then the train whistle!

The train is here. Frank Miller is here. And it’s time. Then the music is over and it’s back to Kane, finishing up the last of his final will and testament.

Holy cow it’s awesome, don’t you think? Note the composition – the arrangement of people in the frame (also called blocking). Everyone is mostly still and really cramped together. This blocking creates a sense of tension, a subconscious claustrophobic effect that amplifies the excitement, especially when coupled with the driving, metronomic music. And as we return to shots (seeing Miller’s gang a second and third time), everyone is even closer together. This is directing at its finest, and a masterstroke of editing, done without flash or fanfare. It’s the one time in the film that is taken out of the real-time context in a way. It’s happening now in present tense, but they are almost all happening simultaneously as opposed to in linear, time-forward sequence.

Holy cow it’s awesome, don’t you think? Note the composition – the arrangement of people in the frame (also called blocking). Everyone is mostly still and really cramped together. This blocking creates a sense of tension, a subconscious claustrophobic effect that amplifies the excitement, especially when coupled with the driving, metronomic music. And as we return to shots (seeing Miller’s gang a second and third time), everyone is even closer together. This is directing at its finest, and a masterstroke of editing, done without flash or fanfare. It’s the one time in the film that is taken out of the real-time context in a way. It’s happening now in present tense, but they are almost all happening simultaneously as opposed to in linear, time-forward sequence.

THE TIN STAR

Professor Cohen, in that great “Intro to Film” class I was talking about, illustrated one shot in this movie that I always think about in my own work. It’s perhaps the greatest shot, or one of the greatest, in American movie history. I say this knowing full well that there is no way to rank this sort of thing. But as a filmmaker, one tries to best use the tools and language of cinema to illustrate emotion through technical means. A great shot is a great shot if it can communicate an emotion but does not draw the viewer out of the film to say “wow that’s a great shot.” If you notice it’s great, it’s probably only doing part of the job it’s supposed to do – too technical, not enough emotional.

Will Kane goes out into the middle of the main street of town. He sees the carriage with his wife go by. He stands in the middle of town, awaiting his fate. And then, the camera starts on a close up of him. And then it pulls back and rises away and up. The music is wary – what’s going to happen next? – and by the end of the shot, we’re looking down at a wide stretch of the town. Kane is the only person there. He’s tiny in the frame, looking around nervously.

He is utterly alone. And he’s screwed.

(Shot starts at 1:10)

The shootout goes on and Kane would definitely have been toast – had it not been for his wife. Amy, who has relinquished violence, hears the first gunshots and runs from the train station back to town. Kane fights in the street and we don’t know where Amy is at all. And then, suddenly, one of Miller’s henchmen goes down. Shot in the back. It’s revealed that Amy pulled the trigger. We see her from behind, and all she does is slump her head. It speaks volumes – for love, she went that far. She violated one of her own principles to save her husband. But not without a personal cost.

Even though this is a singularly unique Western, the good guys still defeat the bad guys. But the end is so good that it cements the film’s place as an unconventional entry into the American Western genre and movie history in general. The townspeople come out after the shootout is over. Kane looks at them, with something like contempt, and throws down his tin star badge. It’s like spitting on the ground in front of them. (It’s badass.) And he takes off with Amy finally – changed, jaded perhaps. He fulfilled his duty, his dharma, as a marshal.

I watched this film recently with my fiancée, who hadn’t seen the film before. She was incredibly surprised that no one came to help. She thought for sure the townspeople would’ve come out in the end, to say something positive about the spirit of community, of people standing up for this heroic figure. You know – good American values that one might expect to find in a traditional Western including loyalty, teamwork, heroism. But the fact that the town people didn’t is what makes this film a true work of literature. Perhaps it says something about human nature, about how we’re willing to send people off to die but less willing when the reality is closer to home.

I watched this film recently with my fiancée, who hadn’t seen the film before. She was incredibly surprised that no one came to help. She thought for sure the townspeople would’ve come out in the end, to say something positive about the spirit of community, of people standing up for this heroic figure. You know – good American values that one might expect to find in a traditional Western including loyalty, teamwork, heroism. But the fact that the town people didn’t is what makes this film a true work of literature. Perhaps it says something about human nature, about how we’re willing to send people off to die but less willing when the reality is closer to home.

What’s interesting to me I just discovered is that people from all sides of the political spectrum have claimed Kane as their own. The film was considered Un-American when it came out seeing that it showed American townsfolk as cowardly – and also possibly an allegory of the McCarthyism and the Red Scare. (The screenwriter was blacklisted, for crying out loud.) John Wayne tried to sink this film because he thought it was the “most un-American thing I had seen in my entire life.” I read that the film was used in Poland’s Solidarity movement to rally support against the Soviet-backed Communists in the first partially free elections there. And now some on The Internet claim Kane as a true American – someone who will go to fight (read: go to war) despite being convinced not to, and that not fighting (like the rest in town) is un-patriotic.

What’s interesting to me I just discovered is that people from all sides of the political spectrum have claimed Kane as their own. The film was considered Un-American when it came out seeing that it showed American townsfolk as cowardly – and also possibly an allegory of the McCarthyism and the Red Scare. (The screenwriter was blacklisted, for crying out loud.) John Wayne tried to sink this film because he thought it was the “most un-American thing I had seen in my entire life.” I read that the film was used in Poland’s Solidarity movement to rally support against the Soviet-backed Communists in the first partially free elections there. And now some on The Internet claim Kane as a true American – someone who will go to fight (read: go to war) despite being convinced not to, and that not fighting (like the rest in town) is un-patriotic.

All of this is hooey.

How on earth could this film be both Communist and Anti-Communist, as well as un-American and uber-American simultaneously? It’s either the most muddled film ever made, or people are idiots. (Okay there’s probably a third category in there someplace…)

But seriously – have these people actually paid attention to this movie? Will Kane is scared! It’s written on his face throughout. He’s not sure if he’s doing the right thing the entire time. He questions himself, isn’t sure if he is right. He thinks he’s done good in town but everyone seems to think otherwise. Gary Cooper as Kane is not a big shot braggart like John Wayne in pretty much every movie The Duke is in. Cooper’s Kane is deeply conflicted and scared but is bound by dharma, (like Rama) and that is what drives him. He’s not boldly growling, “Hey, I’m going to save this town, bitches! YEEEHAW!!!!” He’s saying – “Crap – I’m the marshal. Which sorta sucks because it’s my last day, but I’ve got to do it. Who’s with me? Wait – no one? Seriously?”

But seriously – have these people actually paid attention to this movie? Will Kane is scared! It’s written on his face throughout. He’s not sure if he’s doing the right thing the entire time. He questions himself, isn’t sure if he is right. He thinks he’s done good in town but everyone seems to think otherwise. Gary Cooper as Kane is not a big shot braggart like John Wayne in pretty much every movie The Duke is in. Cooper’s Kane is deeply conflicted and scared but is bound by dharma, (like Rama) and that is what drives him. He’s not boldly growling, “Hey, I’m going to save this town, bitches! YEEEHAW!!!!” He’s saying – “Crap – I’m the marshal. Which sorta sucks because it’s my last day, but I’ve got to do it. Who’s with me? Wait – no one? Seriously?”

If he was truly a win-at-all-costs guy, he would’ve gladly taken the help of that kid. And he would’ve insisted the deputy sheriff stand and fight instead of saying, “Go on home to your wife and kids, Herb” after Herb gives the old hey-I-thought-there-would-be-more-of-us-look-I’ve-got-a-family-to-think-about excuse. Kane isn’t someone who wants to fight, this is someone who now has no choice.

Arguably, if Kane had left at the beginning and Miller comes into town, causes some mischief – the new marshal will come in and fight Miller off, most likely. I don’t think Miller could restart a reign of terror in a few short days. But Kane makes a choice that he’s still marshal and, ultimately, finds out that it’s all on his shoulders for real. If anything, this is an exploration of personal fear and duty. He ultimately is courageous, standing up to true, primal fear we see in that great high angle shot and in close-ups throughout. But it’s not without a recognition of his own frailty, morality, and a questioning of himself. He falls back on his dharma and fights.

I think we can all relate to Kane. Most of us have found ourselves with something on our plate or down the road, coming on a metaphoric noon train, that we are terrified to do. It’s unavoidable and it might hurt or destroy us (again – speaking metaphorically here). But we have to face it. And often we have to face it alone, like Will Kane, and confront our fear.